Translate this page into:

Effect of age and flying experience on heart rate response of fighter aircrew during high-G exposure in the high-performance human centrifuge

*Corresponding author: Ajay Kumar, Department of Acceleration Physiology and Spatial Orientation, Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Indian Air Force, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. ajay4757giri@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kumar A. Effect of age and flying experience on heart rate response of fighter aircrew during high-G exposure in the high-performance human centrifuge. Indian J Aerosp Med 2023;67:2-7. doi: 10.25259/IJASM_62_2020

Abstract

Objectives:

Institute of Aerospace Medicine Indian Air Force regularly conducts high-G training in the human rated high-performance human centrifuge (HPHC) for fighter aircrew. It was hypothesized that the cardiovascular response of young and inexperienced pilots who undergo training in the HPHC may be different from the elder and experienced pilots as age and flying experience may have some effect on the CVS response to high-G exposure.

Material and Methods:

A retrospective analysis of the heart rate data from the data bank of the department of acceleration physiology and spatial orientation was done to understand differences in heart rate response between young and older fighter aircrew.

Results:

A total of 624 successful HPHC runs were evaluated for the baseline heart rate (before high-G exposure), peak heart rate (PHR) (during the exposure), and heart rate after the exposure of the run. The mean age, height, and weight of the subjects were 27.62 ± 5.5 years, 175.31 ± 4.8 cm, and 72.81 ± 8.4 kg, respectively. Student’s t-test revealed that there was a significant difference in the basal heart rate and PHR during the high-G exposure between young, inexperienced, and older experienced pilots. Higher basal heart rate and PHR during high-G exposure among younger pilots could be explained by anxiety due to inexperience and a tendency to pull harder in comparison to other pilots who with experience tend to be more adjusted and pull slower to meet the desired G-level during the high-G training.

Conclusion:

The cardiovascular response during exposure to a high-G environment is significantly different between young, inexperienced pilots, and other senior pilots.

Keywords

Heart rate

High-G

Human centrifuge

Fighter aircrew

Flying experience

INTRODUCTION

The fighter aircrew is regularly exposed to sustained high +Gz acceleration of varying magnitude and durations. Exposure to sustained high Gz acceleration has a significant effect on the cardiovascular system which manifests as a spectrum of symptoms, namely, peripheral light loss and central light loss to G-induced loss of consciousness.[1] These manifestations are due to circulatory disturbance which is the result of simple Newtonian physics applied to the fluid compartments within the body. Exposure to high +Gz acceleration produces immediate changes in the distribution of pressure in the arterial and venous systems, which, in turn, induces shift of blood toward the more dependent parts. These initial disturbances evoke reflex compensatory responses involving the arterial baroreceptors and possibly also the low pressure cardiopulmonary receptors and arterial chemoreceptors. In addition, exposure to acceleration may modify activity in skeletal muscle mechanoreceptors and metaboreceptors, lung-stretch receptors, and vestibular receptors, leading to modulation of cardiovascular function.[2] These responses may be affected by age just like all other physiological functions. Cardiovascular response in terms of heart rate is the most commonly and easily monitored parameter which may reflect the cardiovascular changes under high +Gz conditions.[3]

On exposure to a sustained high +Gz environment, the cardiovascular response of younger pilots and other experienced pilots may differ due to a variety of factors, namely, age (the resting vagal tone is higher with age), anxiety, and handling of the aircraft (younger pilots are likely to be more aggressive). Understanding the differences in cardiovascular responses between younger and other experienced pilots would allow better monitoring of parameters and development of safety protocol during training in the high-performance human centrifuge (HPHC).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The Institute of Aerospace Medicine Indian Air Force (IAM IAF) regularly conducts training of fighter aircrew in an 8 m arm human rated HPHC. Heart rate (in beats per minute) is the basic parameter that is continuously monitored during such training. The details of high-G training at IAM IAF are published elsewhere.[4] For the purpose of this study, the pilots of the age group 20–25 years were considered “young pilots” and the rest were considered “elder pilots.” Although experience comes with age, it also corresponds to rank and flying hours. Hence, these aspects were studied separately. The under trainee (U/T) and UT operational pilots (U/T Ops) were considered “inexperienced pilots” and the rest (Fully operational or Fully Ops, Supervisors, and Senior Supervisors) were considered “experienced pilots.” The attributes were also studied among pilots with flying hours <250 h and others having more than 250 h. These pilots were exposed to all the high-G conditions in the HPHC, while wearing five bladder cut-away type anti-G suits (AGS) and performing AGSM (L-1 maneuver) except during the GOR run, where their relaxed G-tolerance was measured without AGS. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 20 with a confidence interval of 95% and significance value set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 624 HPHC runs were analyzed from the database for base-line heart rate (BHR) (heart rate at 1.4 Gz which is the baseline for the HPHC), peak heart rate (PHR) during the exposure to the G-profile, and post exposure heart rate (HR_PR). The descriptive data for the same have been shown in Table 1.

| Attributes | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Nature of parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 624 | 27.62 | 5.545 | Physical |

| Height (cm) | 554 | 175.31 | 4.834 | Physical |

| Weight (kg) | 554 | 72.81 | 8.384 | Physical |

| G_onset_ROR (G/sec) |

532 | 1.4524 | 1.64113 | Operational |

| Flg_Hrs | 533 | 802.59 | 821.749 | Operational |

| Baseline_HR | 614 | 107.10 | 21.731 | Physiological |

| Peak_HR | 624 | 207.12 | 27.173 | Physiological |

| HR_Post_Run | 595 | 124.08 | 27.247 | Physiological |

| Peak_HR_GOR | 68 | 166.8088 | 34.77143 | Physiological |

| Peak_HR_ROR | 556 | 212.0468 | 21.43579 | Physiological |

| Post_run_HR_GOR | 67 | 105.0149 | 23.96556 | Physiological |

| Post_run_HR_ROR | 528 | 126.4962 | 26.69833 | Physiological |

Age and heart rate response

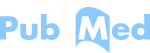

Mean age, height, weight, flying hours, G-onset rate, baseline, peak, and post-run heart rates of the young pilots and elder pilots are shown in [Table 2]. The mean heart rate was higher in younger pilots in comparison to elder pilots. Age-wise distribution of the pilots in the study is shown in [Figure 1]. [Figure 2] shows age-wise distribution of heart rates and G onset rate.

| Attributes | Young_Elder Pilots | N | Mean | Std. deviation | Std. error mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Young Pilots | 258 | 22.78 | 1.367 | 0.085 |

| Elder Pilots | 365 | 31.02 | 4.777 | 0.250 | |

| Height (cm) | Young Pilots | 191 | 174.22 | 5.033 | 0.364 |

| Elder Pilots | 362 | 175.88 | 4.637 | 0.244 | |

| Weight (kg) | Young Pilots | 191 | 67.26 | 5.911 | 0.428 |

| Elder Pilots | 362 | 75.72 | 8.017 | 0.421 | |

| Flg_Hrs | Young Pilots | 192 | 243.46 | 85.275 | 6.154 |

| Elder Pilots | 347 | 1089.15 | 881.029 | 47.296 | |

| G_Onset_Rate (G/sec) | Young Pilots | 244 | 1.6021 | 1.84290 | 0.11798 |

| Elder Pilots | 355 | 1.0939 | 1.38249 | 0.07337 | |

| Baseline_HR (beats/min) | Young Pilots | 252 | 109.73 | 25.478 | 1.605 |

| Elder Pilots | 361 | 105.23 | 18.507 | 0.974 | |

| Peak_HR | Young Pilots | 258 | 210.18 | 24.123 | 1.502 |

| Elder Pilots | 365 | 204.92 | 29.000 | 1.518 | |

| HR_Post_Run | Young Pilots | 244 | 126.23 | 29.067 | 1.861 |

| Elder Pilots | 350 | 122.57 | 25.880 | 1.383 | |

| Peak_HR_GOR | Young Pilots | 58 | 167.8621 | 35.68992 | 4.68632 |

| Elder Pilots | 10 | 160.7000 | 29.74727 | 9.40691 | |

| Peak_HR_ROR | Young Pilots | 224 | 213.2723 | 21.19061 | 1.41586 |

| Elder Pilots | 331 | 211.2205 | 21.62482 | 1.18861 |

- Age-groups and number of pilots in the study.

- Age-wise (in years; X-axis) G-onset rate (G/sec) and heart rates (in beats per min) of the pilots in the study.

ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that there was a significant difference in PHR among the pilots of the age-group 20–25 years and 31–35 years (P = 0.001) and 26–30 years and 31–35 years (P = 0.006). Young pilots pulled significantly faster (G-onset rate higher) than the elder pilots; t (156.8) = 6.72; P = 0.000.

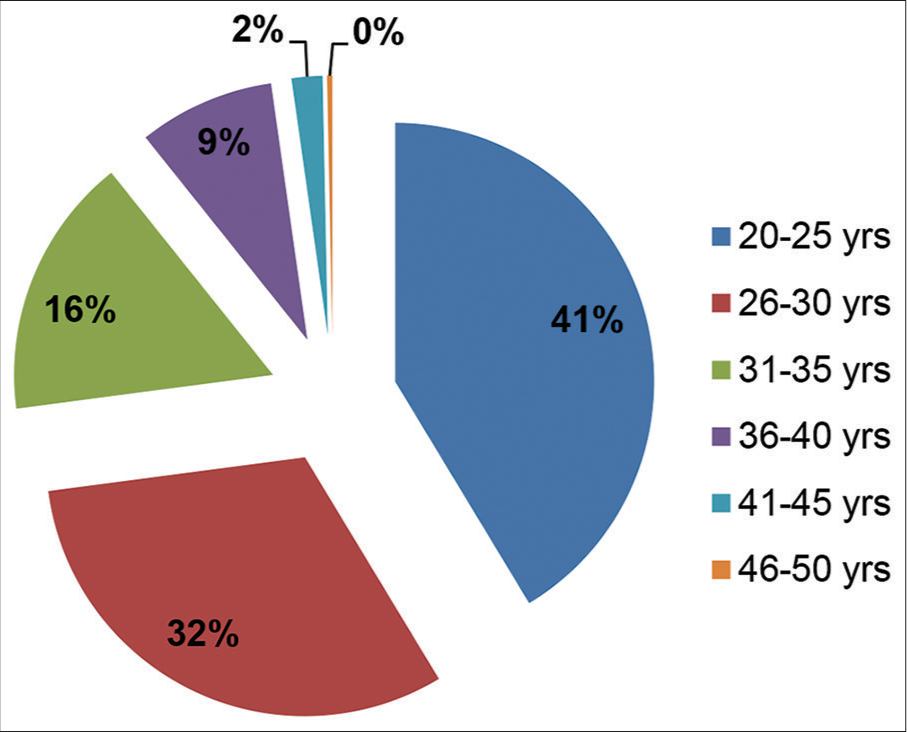

Rank and heart rate response

The rank-wise distribution of the pilots in the study is shown in [Figure 3].

- Rank-wise distribution of the pilots in the study.

The mean age of inexperienced pilots was 24.5 ± 2.7 years and the experienced pilot was 34 ± 4.3 years. Independent samples t-test revealed that experienced pilots were taller and heavier than the inexperienced pilots and pulled G slower than the inexperienced pilots. Heart rate responses were higher among the inexperienced pilots. However, a statistically significant difference was observed only in BHR and PHR (P < 0.01).

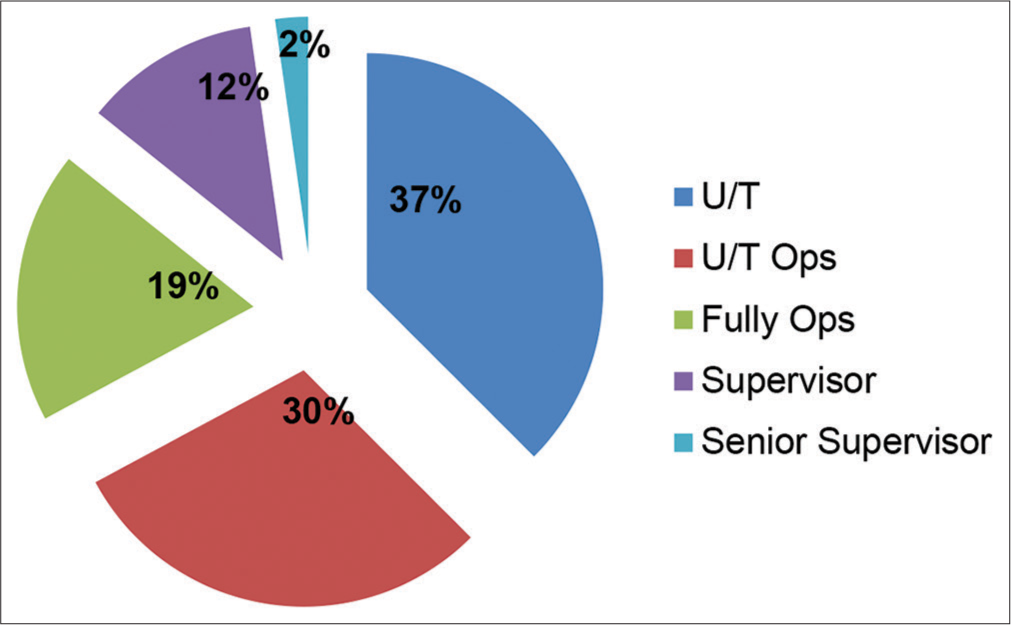

Flying hours and heart rate response

The total number of pilots whose data were analyzed based on flying hours in the study is shown in [Figure 4]. The mean age of the pilots with flying experience of 250 h and less was 23.43 ± 2.7 years and 30.06 ± 5.17 years for others. The heart rate responses (BHR, PHR, and heart rate post-run) were significantly higher among the pilots having flying experience of 250 h or less (P < 0.01).

- Flying hours and number of pilots in the study.

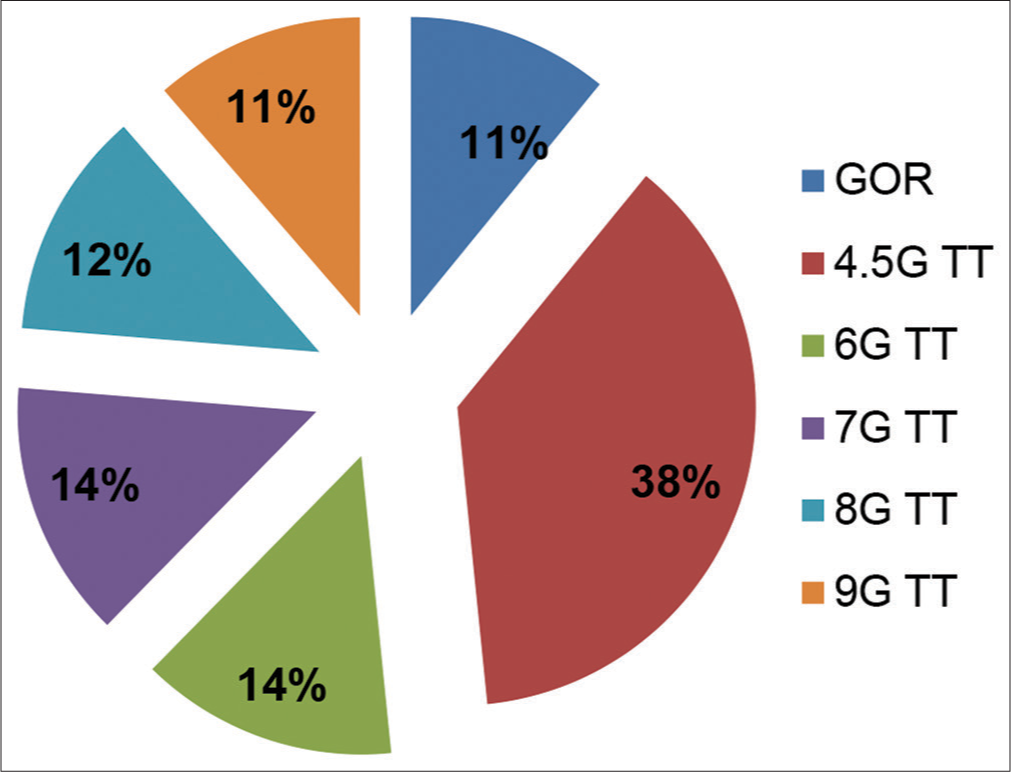

HPHC runs and heart rate response

[Figure 5] shows the various HPHC runs that were analyzed in the study.

- G-levels exposed to the pilots during the HPHC runs. HPHC: High-performance human centrifuge.

The G-onset rate and heart rate response during various G-levels in the HPHC are shown in [Figure 6].

- G-onset rate and mean heart rate (HR/100) during exposure to HPHC runs in the study (TT is target tracking controlled by pilots). HPHC: High-performance human centrifuge.

Spearman’s correlation [Table 3] showed statistically significant negative correlation of heart rate responses with age and flying hours.

| Attributes | Flg_H | G_onset | BHR | PHR | HR_ PR | PHR GOR | PHR ROR | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flg_H CC Sig N |

1 533 |

−0.172** 0.000 523 |

−0.146* 0.000 524 |

−0.19** 0.000 533 |

−0.145** 0.001 509 |

−0.336** 0.006 56 |

−0.162** 0.000 477 |

0.860** 0.000 533 |

| G_onset (G/sec) CC Sig N |

−0.17** 0.000 523 |

1.000 . 600 |

0.276** 0.000 590 |

0.081* 0.024 600 |

0.229** 0.000 571 |

Constant GOR | −0.083* 0.028 532 |

−0.187** 0.000 600 |

| BHR CC Sig N |

−0.15** 0.000 524 |

0.276** 0.000 590 |

1.000 . 614 |

0.214** 0.000 614 |

0.526** 0.000 587 |

0.139 0.129 68 |

0.116** 0.003 546 |

−0.146** 0.000 614 |

| PHR CC Sig N |

−0.19** 0.000 533 |

0.081* 0.024 600 |

0.214** 0.000 614 |

1.000 . 624 |

0.307** 0.000 595 |

1.000** 0.000 68 |

1.000** 0.000 556 |

−0.154** 0.000 624 |

| HR_ PR CC Sig N |

−0.15** 0.001 509 |

0.229** 0.000 571 |

0.526** 0.000 587 |

0.307** 0.000 595 |

1.000 . 595 |

−0.089 0.247 61 |

0.087* 0.023 530 |

−0.093** 0.012 595 |

| PHR GOR CC Sig N |

−0.34** 0.006 56 |

Constant GOR | 0.139 0.129 68 |

1.00** 0.000 68 |

−0.089 0.247 61 |

1.000 . 68 |

−0.292** 0.008 68 |

|

| PHR ROR CC Sig N |

−0.16** 0.000 477 |

−0.083* 0.028 532 |

0.116** 0.003 546 |

1.00** 0.000 556 |

0.087* 0.023 530 |

1.000 . 556 |

−0.134** 0.001 556 |

|

| Age (years) CC Sig N |

0.860** 0.000 533 |

−0.187** 0.000 600 |

−0.146* 0.000 524 |

−0.15** 0.000 624 |

−0.093** 0.012 595 |

−0.292** 0.008 68 |

−0.134** 0.001 556 |

1.000 . 624 |

The mean maximum target heart rate (often used in exercise testing) for age (i.e., 220-age) during GOR and ROR would be 192 ± 6 bpm and 193 ± 6 bpm, respectively. The mean PHR attained during GOR was significantly lower (87% of mean maximum heart rate) than the mean of maximum target heart rate for age (P < 0.001) and the mean PHR attained during ROR (P < 0.001) was significantly higher (110%) than the mean of maximum target heart rate for the age. PHR was significantly higher for young and inexperienced pilots as well as Ab Initio and other pilots in comparison to the expected target heart rate (P < 0.05). However, this rise in the heart rate was not significantly different between young and inexperienced pilots as well as Ab Initio and other pilots in the study (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The cardiovascular system has evolved to be extremely dynamic and responsive to the stress of orthostasis in the human body. If the orthostatic stress is magnified in the form of sustained exposure to a high +Gz environment (>2 s), the cardiovascular system’s dynamism and responsiveness are stretched to their limits. Rowell has concluded that the performance of the heart under G stress is determined primarily by peripheral circulation.[5] The compensatory changes under such conditions are mediated through a closed loop baroreceptor reflex based on autonomic nervous system (ANS) response. The baroreceptor sensitivity (gain) is modified by various factors including advancing age and arterial wall distensibility (which also becomes less distensible with advancing age).[1] This results in a significant reduction in heart rate response with age as aging itself could disrupt ANS through reduction and increase in the input of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, respectively.[6,7] The ANS controls cardiac functions by activating its efferent sympathetic nerves to increase heart rate and contractility.[8] In addition, the parasympathetic nerves exert control over heart functions through a direct vagal mediated reduction in heart rate (bradycardia).[9] The ANS promotes rapid adjustments of the cardiovascular system during orthostasis and high-G stress. The age-related disruption in ANS may affect this adjustment. However, the course of normal aging could be altered by physiological conditioning.[10] Aerobic conditioning is also known to reduce heart rate. Hence, the age-related cardiac response may also get modified by the aerobic fitness of aircrew which may get pronounced with age.

The heart rate responses during ROR runs were significantly higher than GOR runs. The raised BHR could be attributed to the higher baseline G level (1.4 G) as well as excitement in anticipation of the immediate G-exposure (psychogenic) as reported by Parkhurst et al. and Leverett et al.[3,11] There was a significant rise in heart rate during exposure to high-G which remained elevated post-run. It was significantly higher among the young and inexperienced pilots who are probably due to the tendency to pull harder in comparison to other pilots who with experience tends to be more adjusted and pull slower to meet the desired G-level during the high-G training.

Age and experience (flying hours) had a significant negative correlation with baseline, peak, and post-run heart rate responses [Table 3]. Although there were a significant difference in PHR and post-run heart rate responses between pilots of 20–30 years and 31–35 years, this relationship was not consistent among elder pilots. This could be due to the insufficient no of subjects in the higher age groups (41– 45 years had 12 and 46–50 years had only two pilots). The PHR response appears to be the result of the combined effect of G onset rate, G level, duration of G exposure, the intensity of AGSM, use of AGS, age, and flying experience of the pilot which, in turn, also affects the recovery heart rate post-run.[3] These factors may not be significant in isolation as revealed by low to negligible correlation, which, however, may affect cardiovascular response significantly if acted together in combination.[12] Furthermore, the PHR was not significantly different during various ROR runs (4.5G TT–9G TT). This could be due to the effective anti-G straining maneuver (AGSM) performed during such runs with similar intensity despite the differing G-levels.

The mean PHR during the ROR run was much higher (110%) than the maximum target heart rate calculated by the formula 220-age given by Fox et al. to indicate exercise intensity.[13] At the same time, the PHR attained was 87% of the maximum target heart rate during the GOR runs as subjects were relaxed and no AGSM was performed during such runs. This heart rate response appears to be independent of the age and experience of pilots as the rise in heart rate was not significantly different between young and experienced and Ab Initio and other pilots. The heart rate response gives a glimpse of the intensity of stress the cardiovascular system has to undergo to endure a high-G environment.[14] The cardiovascular system of even a relaxed sitting subject during a GOR run is stressed to a workload akin to Zone 4, that is, a hardcore anaerobic training zone. This stress reaches a maximum effort zone when the subject performs AGSM in the high-G environment. This could be because lung compliance reduces due to increased abdominal pressure during sustained exposure to high-G. The AGS and AGSM, further, aggravate the reduction in lung compliance. The reduced compliance and increased weight of the chest wall structures increase the work of breathing in proportion to increased +Gz. Glaister reported that a total increase of 55% in the work of breathing occurs at +3Gz.[15] This could alone explain the cardiovascular stress imposed on a relaxed seated subject akin to a hardcore anaerobic training zone during GOR runs. This observation re-emphasizes the need for anaerobic physical conditioning for fighter pilots.

CONCLUSION

The heart rate responses of younger and inexperienced pilots were significantly higher than the elder and experienced pilots. The higher BHR among younger pilots could be psychogenic due to inexperience and higher baseline G level. The higher PHR among younger pilots could be due to inexperience and a tendency to pull harder during high-G training.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent is not required as patients identity not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Long duration acceleration In: Gradwell DP, Rainford DJ, eds. Ernsting’s Aviation and Space Medicine (5th ed). Florida: CRC Press; 2016. p. :131-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- G-transition effects and their implications. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001;72:758-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiologic Responses to High Sustained +Gz Acceleration, 777604 France: AGARD; 1973.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of G-induced loss of consciousness and almost loss of consciousness incidences in high-performance human centrifuge at Institute of Aerospace Medicine Indian Air Force. Indian J Aerosp Med. 2019;63:3-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spectral characteristics of heart rate variability before and during postural tilt. Relations to aging and risk of syncope. Circulation. 1990;81:1803-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Components of heart rate variability: Basic studies In: Malik M, Camm A, Futura A, eds. Heart Rate Variability. Armonk, NY: Futura; 1995. p. :147-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adrenergic nervous system in heart failure: Pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2013;113:739-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmias: Role of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:S94-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageing-induced biological changes and cardiovascular diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2018;208:7156435.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (5th ed). Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physical activity and the prevention of coronary heart disease. Ann Clin Res. 1971;3:404-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of Gravity and Acceleration on the Lung London: NATO Advisory Group for Aerospace Research and Development; 1970.

- [Google Scholar]