Translate this page into:

Prevention of suicide: The IAM awarence training programme

Abstract

During the period 1991-1996, the incidence of suicide were on the increase in the Training Establishments of the Air Force. As a large number of these suicide victims were ab-initio airmen trainees, preventive measures to arrest this trend become a matter of serious concern in the Airmen Training Institutes. One of the immediate remedial measure taken was to assign groups of trainees to one mentor. The ‘mentoring’ system was already in existence in these Institutes and therefore to facilitate awareness in this group, the mentor population was chosen as the target for indoctrination. During the years 1997-2003, thirty workshops were conducted to educate over 600 mentors and instructional staff on various aspects of suicide and to provide guidelins for prevention and management. The overall objective of the workshops, which are still being conducted regularly is to provide awareness training to help mentors identify and prevent sucide in the workplace and environment. The methodology utilized for training in the workshops are lectures, visual aids, group discussions, case studies, post workshop assessment and feedback, compilation and communication of feedback to higher administrative authorities and evaluation of outcome effects. There have been no successful suicides in the trainee population since 1999. The paper outlines the possible reason for the decreased incidence of successful suicides. However, suicide attempts may still occur in the airmen training establishments and a reduction in these is also needed. This paper also identifies the types of changes required for future modification of the present prevention stategy, to help perfect it and achieve training goals through the use of ongoing intervention and surveillance monitoring activities.

Keywords

Mentor

Intervention

Military

Suicide

Suicides are a major public health burden in all countries of the world and more so in developing countries like India [1]. It has become all important global concern with the increasing occurrence of suicide amongst youth in both developing and industrialised countries. The only source of information in India has been from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) which reported in the year 1999, the national suicide incidence rate is 111,00,000/yr, with young adults (15-29 yrs) contributing to 37% of this number [2]. In India, the problem is more complex to define because of paucity of information, as there is a complex interaction of social, health, economic, demographic and environmental factors. This makes development of intervention stategies more difficult [3,4].

In the military, a number of countries not only acknowledge the presence of the problem of suicide in their armed force [5,6] but also have devised effective suicide prevention strategies [5,7]. For example, during the years 1990-1994, the annual suicide rate among active duty United States Air Force (USAF) personnel increased significantly (p<0.01) from 10.0 to 16.4 suicides per 1,00,000 members. In 1995, senior USAF leaders initiated prevention programmes in several commands because of the increasing suicide rate.

The suicide prevention strategy encompassed nearly all the USAF community (e.g. investigative agencies, military justice, and prevention and treatment services) and focused on reducing suicide by emphasising early interventions and strengthening protective factors (e.g. a sense of belonging and caring, effective coping skills and policies that promote help-seeking behaviour).

The initiatives were divided into three categories corresponding to areas identified by other prevention programmes: Center’s for Disease Control (CDC) recommendations for youth suicide prevention [8] were adapted to the USAF adult population. The team established USAF requirements for annual suicide prevention and awareness training, which was provided to approximately 80% of USAF members. Supervisors and leaders within each military unit, medical providers, attorneys, and chaplains received concentrated training as ‘gatekeepers’ whose role was to channel persons at risk to appropriate agencies. Secondly, prevention services offered on USAF installations were restructured [9] and a central surveillance database for fatal and non fatal self-injuries [10] was established. As a result from 1994 to 1998, the suicide rate among USAF members decreased significantly, from 16.4 suicides per 1,00,000 members to 9.4 (p<0.002).

The efficiency of any organisation depends on a number of variables. In the service set up, monitoring of diseases/disabilities rates are relatively more efficient and organised. Prevention of illnesses, injuries either self or other inflicted and accidents is of prime importance in the continued development of the people in the organisation. The combined responsibilities of both authorities and all personnel are pivotal in this developmental role. In the midst of the complex (and often strongly resisted) process called change, are the trainers. The change required may be as broad and pervasive as a new direction in organisational strategy or as immediate and personal as helping someone to master new job skills. Whatever the magnitude, trainers are change agents helping others into the future [11].

Education and training are key components of any suicide prevention programme. This includes risk identification training. Supervisors need to know how to identify people who are at risk and how to help them. To help supervisors do that, suicide prevention training can be provided through buddy care classes, professional military education, commander’s and supervisor training. Support personnel and health care providers can also receive training in suicide prevention, helping them to learn how to better recognise problems and make the right referrals. Also, identification and referral can be carried out by two levels of ‘gatekeepers’, a concept put forward by the CDC, at the unit and community levels.

The overall incidence of suicide in Indian Air Force (IAF) personnel, during the years 1991-2002 varied between 8.2 to 14.8/1,00,000/year.

Of the individuals who took the extreme step ofending their lives, a substantially large number of these persons were ab-initio airmen trainees of various training institutes. In twenty one of these cases, the reasons for committing suicide were frustration, financial, family and matrimonial problems, guilt and psychiatric problems. During the period 1997-2003, the incidence in the Training Command varied from zero to five per year.

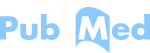

No aircraftsmen under training (AC/UT) have been victims of suicide since the year 1999. This change was brought about because some of the causes and effects of suicides in ab-initio airmen trainees were examined and a training strategy was devised, which was appropriate to the objective of prevention in this subpopulation of TC as shown in Fig 1.

- Training strategy for suicide prevention in 1997

Steps 1 and 2

The training process began in 1997, when preventive measures to arrest the alarming trend of suicides became a matter of serious concern in the airmen training institutes. Consequently, a number of training directives were issued by Head Quarters (HQ) TC. These brought to notice that precious young lives were being lost and victim’s family trauma could have been prevented in some cases if symptoms had been detected early and remedial measures implemented. One of the immediate remedial measures suggested was that groups of trainees “will be assigned to one mentor who will be their ward”. The ‘mentoring’ system was already in existence in these institutes. All instructors in the training establishments are given the additional duty of mentoring. They meet their wards at regular intervals and counsel them if the need arises. The number of these meetings are maintained in a logbook. One mentor may have between ten and thirty wards whom they counsel all through the training phase.

The other remedial measures recommended at that time were: the institution of the ‘buddy system’, group activities for trainees, more active communication and interaction with trainees by commanders and commanding officers and improvement in responsiveness and responsibility of instructors to individual problems of trainees at both professional and personal levels.

Later, as the outcome of ‘Brainstorming Sessions’ held at a peripheral station, certain recommendations were again put forward to address the issue of measures to prevent suicide. Immediate measures included the buddy system, monitoring the progress of the trainees and records in the form of confidential dossiers with elaborate personal information as well as the trainee’s behaviour and progress in the training centre. Long term measures suggested were : addressing both medical and psychological issues at the time of selection and a feedback system. For trainees the measures were: gradual regimentation, regular contact with parents, sports and hobbies, break after first term and counselling by trained psychologists. This was followed by another training directive, which outlined the possible causes that push the trainees to committing suicide and the symptoms that they may manifest.

Steps 3-10

The TC indicated that training staff in the airmen training establishments could be trained by clinical psychologists to identify potential cases of suicide and asked Institute of Aerospace Medicine (IAM) to put up a proposal for conducting a capsule course to train instructional staff. To facilitate awareness in these groups, the mentor and officer populations were chosen as the target groups for indoctrination. A proposal was put up by IAM, for starting the courses and the Dept of Aviation Psychology, initially conducted six, four day orientation workshops between December 1997 and May 1998 to educate the mentors and instructional staff on various aspects of suicide and to provide guidelines for prevention and management.

No courses were conducted in IAM in 1999. In November 1999, a ten day intensive workshop was conducted at Jallahalli by the Departments of Clinical Psychology, Psychiatry and Psychiatric Social Work, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS,) Bangalore.

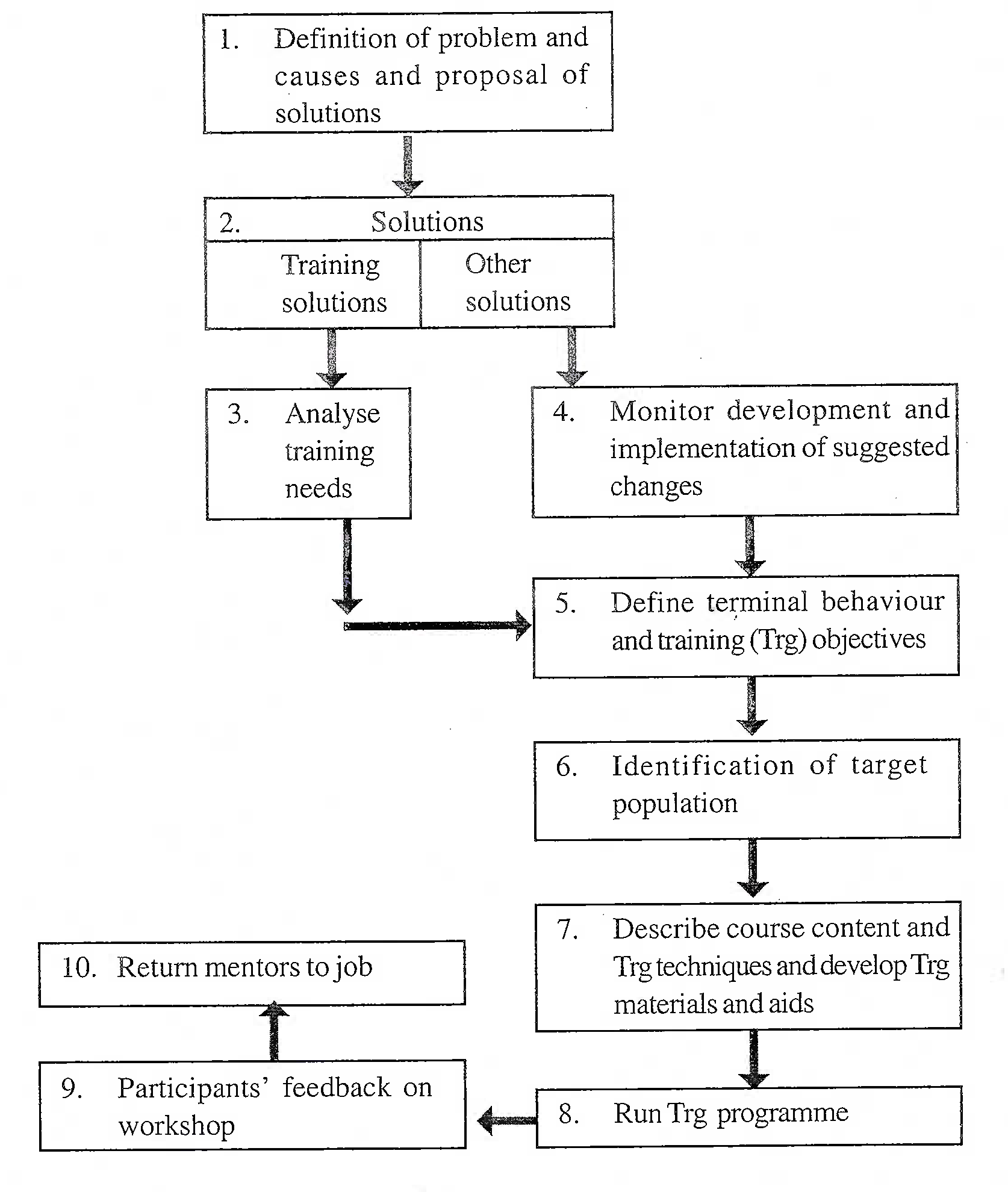

During the years 2000-2003, 24 four day workshops have been jointly conducted by Dept of Aviation Psychology, in the Training Wing at IAM, with guest lectures from NIMHANS faculty and Command Hospital Air Force Bangalore (CHAFB) psychiatrists. More than 600 mentors have been trained. In the year 2000, more planning and evaluation tools were proposed. This paper discusses the next stages involved in the development of an awareness-training model (Fig 2) for the target population.

- IAM Awareness training process

Training Objectives, Goals and Target Population

The overall objective of the workshops is to help mentors identify and prevent suicide in the workplace environment. Revision of Step 5 was carried out when the specific goals of the training programme were objectively defined and modified:

To orient mentors about the psychology of youth and psychosocial and mental health problems of AF trainees.

To impart knowledge about counselling approaches, skills and techniques.

To facilitate mentors sharing then-experiences in helping AF trainees.

During the workshops emphasis is placed on certain aspects that would promote learning and spontaneous group interaction and participation. The first is a three-way learning process; instructor to participants, participants to instructors and participants between themselves. Flealthy group interaction among the participants who may be from different ranks is not only encouraged, but forms the second important aspect of the workshop. Thirdly, the experience gained through these workshops should initiate and promote personal growth leading to self-awareness and openness to experience, the most effective basis of being able to empower oneself and consequently, others.

Mentors and directing staff have an important role as effective and trustworthy counsellors and guides. It is essential for the mentor not only to understand the emotional state of the trainee but also his own role as a counsellor. The mentor is described as a significant transitional figure that represents skill, knowledge and accomplishment while serving as a guide and teacher, to the protege [12]. One of the important functions of mentoring is the psychosocial function [13,14], Psychosocial functions are defined as “those aspects of relationship that enhance a sense of competence, clarity of identity and effectiveness in the professional role”. These are seen to be interpersonal in nature and involve role modelling, acceptance, and confirmation, counselling and friendship. In the year 2001, the target population was restricted to only the mentor population and no officers were detailed for the courses (Revision of Step 6), after IAM informed HQ, TC that mixing of both groups for workshops was proving to be counterproductive to the group behaviour and interactions during the course.

Methodology and Training Evaluation

The methodology utilised for training in the workshops were lectures, visual aids, group discussions and case studies. Post workshop assessment and feedback, compilation and communication of feedback to HQ TC and evaluation of outcome effects were introduced in 2000.

Course Content

The course content of the workshop covers four main topics: the psychological state of the adolescent, psychological life stresses, definition and explanation of suicide. More classes on aspects of counselling were introduced in 2000. NIMHANS faculty were invited for a full days’ lectures to cover counselling topics (Revision of Step 7). A total number of 20 hours of lectures are taken, and there is a minimum of four hours of group discussion and case studies. Lecture notes on all topics were printed and provided in 2000.

The trainees recruited to the training institutes are usually in their late adolescence. The adjustment to the new surroundings and life style may pose a host of difficulties. The discipline and the controlled emotional atmosphere of a training institute and the fact that most of the trainees leave their homes and families for the first time may induce stress and cause maladjustment. The first topic deals with the normal developmental changes that take place during adolescence.

Different psychological life stressors, which occur at both the individual and organisational levels and strategies to overcome these, are discussed. When an individual is unable to cope up with these stressors, he may begin to feel, think and act in a different way. The identification of these behavioural changes, which may finally end in suicidal ideation and an attempt, is also elaborated.

The definition, explanation and prevention of suicide, forms the third topic and covers the medicolegal and organisational procedures involved and psychological and sociocultural factors, which may predispose an individual towards attempting to take his own life.

In the whole process, the mentors play a crucial role by the interaction and help they render to the trainees through counselling. Counselling skills are dependent on one’s own level of self-awareness combined with the knowledge and skills of psychological techniques. The last topic outlines the basic principles of counselling giving a general idea about the goals, process and techniques involved in counselling. However, presently Only theoretical and little practical information is given on counselling.

Post Workshop Assessment and Feedback to TC

In the year 2000, in addition to feedback about the course, post workshop assessment forms were made and provided to all participants at the end of the workshop, when one hour is spent for post workshop assessment (Step 9). Participants are told to fill in an open-ended questionnaire. The first aim of this assessment was that the instructors could get first hand information about the situation in their training establishments and the participants could themselves identify issues to be tackled and suggest remedial measures for smoother and more effective functioning. The second aim was to assess the extent of participant’s understanding of the basic principles taught after the workshop. This was used only to change the teaching pattern and lecture content, if required.

The information derived from these forms for the first aim, was then tabulated for the most important and recurring issues and grouped under general headings. These were formulated in the form of a “Report of Workshop Assessments for the year 2000” which was forwarded to HQ,TC in June 2001 with recommendations to be implemented [15]. Information was again collected from assessments done in 2001-2003. These important recommendations were again put forward through correspondence in 2003 and are outlined (Updated inputs to Step 4). These revolved around two issues of importance: modification of training environment and feedback and compilation of statistics related to incidence of suicides in TC. In modification of training environment it is recommended that counselling be carried out in a more efficient mariner including imparting of proper training to mentors as counsellors and providing adequate facilities for counselling. Secondly, mentors should be vested with more discretionary powers in tackling the problems of trainees. Most of the trainees’ problems are administrative and presently mentors are unable to help. The regular feedback of suicide related statistics to IAM, IAF Bangalore is also necessary so that training goals can be evaluated.

Six Month Post Workshop Feedback from Participants to IAM

In future, six-month post workshop feedback proformas for mentors need to be given to participants to assess how they have been able to utilise the information derived from the course in actual settings. These will be mailed back to IAM six months after they have attended the course (Step 11). The model requires checking if terminal behaviour is achieved and reviewing the process as part of the last Step 12.

Results and Discussion

The broad objective of the training has been achieved. There have been no successful suicides in this population from the years 1999-2003. Although the absence of successful suicides among airmen trainees corresponds temporally with the workshop programme, a direct causal relation between the two cannot be established conclusively. It seems unlikely that the zero level of incidence in this population is related to national, ail AF, or all TC levels of incidence.

It appears that awareness training given to the mentors may have generated more awareness in the community, since the participants would have learnt about suicide and also disseminated this information to others in their units and outside.

Other indirect indicators of training outcome such as information regarding the number of suicidal attempts and the number of referrals to Depts of Psychiatry at CHAF (B) and Armed Forces Medical College (AFMC) after workshops were begun are provided in Table 1.

| Measures | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of Suicidal attempts | 00 | 00 | 01 |

| No of AC/UT referred for any psychiatric disorders | 00 | 00 | 03 |

| Total AC/UT Population | 3014 | 3015 | 3235 |

However, in addition to this, statistical information regarding the number of suicidal attempts and the number of referrals to Depts of Psychiatry at CHAF(B) and AFMC before workshops were begun, also need to be determined for comparison. Other components that might have also been responsible for this reduction can be identified. These refer to the inputs at Step 4, initially in 1997 and later from reports and communication from IAM in 2001. The remedial measures recommended in 1997 have been instituted: more gradual regimentation, regular contact with parents, the ‘buddy system’ group activities for trainees such as sports and hobbies, and break after first term. Active communication and interaction with trainees by commanders and commanding officers and improvement in responsiveness and responsibility of instructors to individual problems of trainees at both professional and personal levels and monitoring their progress, were other changes, which took place. Record keeping was improved; keeping confidential dossiers with elaborate personal information as well as the trainee’s behaviour and progress in the training centre, were started.

Therefore, it is recommended that a central agency be formed in HQTC, Bangalore to :

Co-ordinate, develop and establish a procedure to capture demographic risk factors and protective factor information pertaining to suicide related information of individuals who have attempted or completed suicide.

Maintain accurate suicide related information.

Monitor feedback provided to HQ TC and all training establishments and

Be responsible for evaluating any changes that are being recommended. Implementation of recommendations and any other modifications required in the training can also be conveyed back to IAM by the same agency.

Summary

The Suicide Prevention Awareness Training was carried out for five years and continues at IAM. Since 1999 there has been a zero incidence of suicide in airmen trainees. This experience highlights that suicide is generally a preventable health problem. It demonstrates the importance and effectiveness of using a training model, to address the issue of changing awareness levels in a target population. It also highlights the long and difficult process in the development of effective suicide prevention methods. However, it is possible for preventive workshop programmes to be planned, implemented and modified within time frames. The degree of efficiency with which such programmes can be carried out is a reflection of the advantages of the hierarchical structure of the organisation, which can bring about disciplined change; contributing to the reduction of self-directed violence.

This paper identifies the type of changes required in the training model to further modify this prevention strategy to help achieve and perfect training goals. These are, introducing more accurate indicators of training outcomes in the form of maintaining accurate suicide related information and establishing an epidemiological database. Monitoring of ongoing intervention and surveillance activities at different levels of organisational structure is necessary for actual implementation. This will help improve general mental health and prevent not only suicides but also suicidal attempts and gestures, which still occur in the airmen training establishments.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to AVM AK Sengupta (Retd) for initiating and being a strong inspiration behind this training programme. We thank AVM KS Soodan (Retd) and Maj Gen JS Kulkami for the permission and support to the programme. The Depts of Psychiatry, CHAFB and IAM were involved in giving lectures on psychiatric aspects of suicide, we are thankful to them for their assistance. We thank all members of the Training Division, IAM for support and help in conduct of the workshops and the service units, HQTC and Air HQ (Med-8) who provided data regarding suicides.

References

- Injury: A leading cause of the global burden of disease.

- Accidental deaths and suicides in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 1999.

- Suicide prevention programs: issues of design, implementation, feasibility, and developmental appropriateness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25:92-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of suicide: Guidelines for the formation and implementation of national strategies. New York: United Nations; 1996. United Nations publication ST/ESA/245

- Suicide Prevention Among Active Duty Air Force Personnel - United States, 1990-1999. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report. 1999;48(46):1053-1057.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of psychopathological factors and origins of suicides committed by soldiers 1989-1998. Mil Med. 2001;166(1):44-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- The assessment and Prevention of Suicide for the 21st Century: The Air Force Communication Awareness Training Model. Mil Med. 2001;166:195-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- Youth suicide prevention programs: a resource guide. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control; 1992.

- The future of public health. Vol 35. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988.

- Public health surveillance in the United States. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1988;10:164-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The training environment and the trainer’s job. In How to be an effective trainer 1987:3-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seasons of a Man’s Life. New York: Ballantine; 1978.

- Mentoring at work: Developmental Relationships in Organisational Life. Lanham MD: University Press of America; 1988.

- Report on Prevention of suicide workshop assessments for the year 2000. Bangalore: IAM, IAF; 2001.