Translate this page into:

Cardiopulmonary responses to centrifuge simulated parabolic flight

*Corresponding author: Dr HS Harshith, MBBS, MD (Aerospace Medicine), Air Force Station Sirsa, Indian Air Force, Sirsa - 125055, Haryana, India. harshith.hs@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Harshith HS, Nataraja MS, Dinakar S. Cardiopulmonary responses to centrifuge simulated parabolic flight. Indian J Aerosp Med 2021;65:57-62.

Abstract

Introduction:

Parabolic flights, by producing short periods of weightlessness, closely simulate microgravity. However, they are still expensive, incur a significant logistics support, and occurrence of any adverse events during such simulation is undesirable. The present study was formulated to explore the feasibility of using a human centrifuge for simulation of parabolic flight to study the cardiopulmonary parameters as an alternative ground-based model.

Material and Methods:

Twelve healthy male volunteers were subjected to simulated parabolic flight, the profile of which involved exposure to 20 repetitions of hypogravity periods (+0.5 Gz), each interposed between periods of hypergravity phases (+2 Gz), using high-performance human centrifuge. Heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) were studied during such a simulation and analyzed using one-way repeated measures ANOVA. Motion sickness assessment questionnaire was administered to the participants after the run. They were also asked to rate their subjective feeling of weightlessness experienced during the run.

Results:

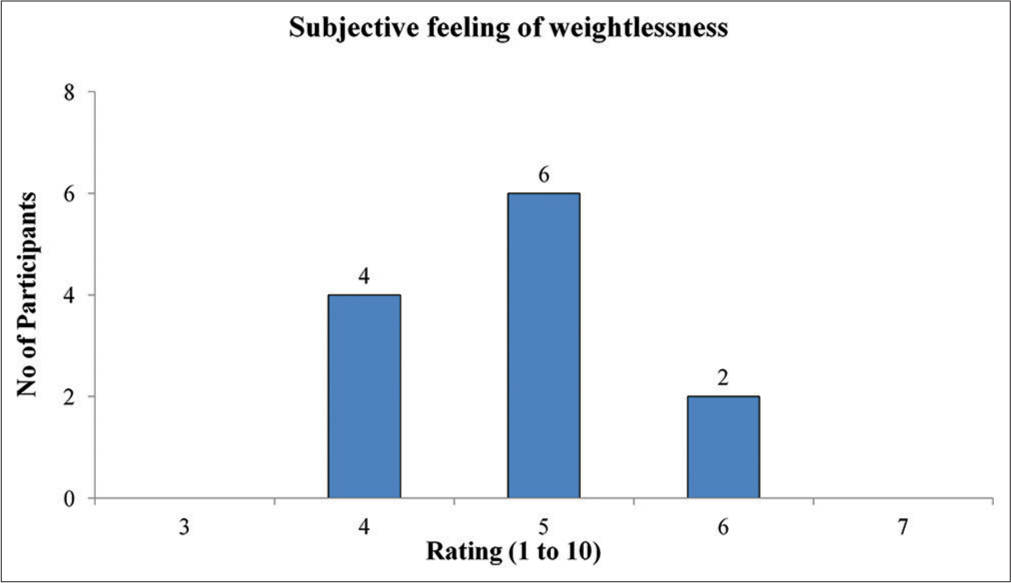

Comparison of HR revealed a significant difference (F = 22.167, P < 0.001) across 20 loops of different gravity phases. Post hoc analysis revealed that the mean HR of hypergravity phases was significantly higher compared with pre-run 1 G values and that of hypogravity phases. Similarly, HR showed a significant difference across pre-run 1 G, 10th and 20th loops of hypogravity phases (F = 5.672, P = 0.01). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant reduction in HR at 20th loop compared to both pre-run 1 G (P = 0.023) and 10th loop (P = 0.042) values. No significant differences were observed in both RR (F = 1.789, P = 0.148) and SpO2 (F = 1.708, P =0.199) across different gravity phases. The mean overall motion sickness score was found to be 23.6%. Participants rated their subjective feeling of weightlessness between 4 and 6 (mode = 5) on a scale of 1–10.

Conclusion:

It can be concluded from the results that HR increased during hypergravity conditions and reduced during hypogravity conditions, an expected outcome during parabolic flight. The significant reduction in HR during the 20th loop of hypogravity phase compared to 10th loop and pre-run 1 G conditions indicate a possible association with the duration of exposure. The centrifuge simulated parabolic flight profile designed in our study was able to emanate physiological changes similar to those experienced in actual parabolic flight for HR, RR, and SpO2.

Keywords

Parabolic flight simulation

Centrifuge

Heart rate

Motion sickness

Subjective experience

INTRODUCTION

Parabolic flights are one of the earliest microgravity simulation models,[1,2] still in use and are capable of producing absolute weightlessness, although for very short durations.[3] They help in providing easy access to conditions of space, wherein, possible adverse issues can be addressed.

Although parabolic flights are more accessible means of achieving microgravity conditions than the actual orbital space flights, they still incur significant financial and logistics burden on any organization. Hence, any unforeseen conditions or adverse events, like severe motion sickness, leading to mission compromise may be undesirable.

Ground-based microgravity simulations and analogs are of paramount importance in both microgravity research and space crew training. A few studies have reported the use of centrifuges for simulation of parabolic flight involving human participants.[4,5] Human Centrifuge, as a simulation modality for parabolic flight, may serve as a training platform for the preparation of space crew for the subsequent actual parabolic flight and space missions by allowing their familiarization and physiological adaptation to such novel environments. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the feasibility of using human centrifuge for parabolic flight simulation. It also aimed to assess the changes in the cardiorespiratory parameters (heart rate [HR], respiratory rate [RR], and arterial oxygen saturation [SpO2]) to simulated parabolic flight using human centrifuge.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Subjects

Twelve healthy male volunteers participated in the study (30 ± 5.2 years, 170.4 ± 7.9 cm and 69.8 ± 9.3 Kg). Participants with known or history of any cardiorespiratory illness or on any medications were excluded from the study. All the participants were explained about the study protocol and were familiarized with the High Performance Human Centrifuge (HPHC) at the Department of Acceleration Physiology and Spatial Orientation at the Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Indian Air Force. A written informed consent was taken from all the participants. The study protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Materials

The HPHC was used to simulate parabolic flight conditions. HPHC is capable of producing multiaxial accelerations and has medical monitoring facilities. Equivital wireless physiological monitoring system was used to record HR and RR. The system includes a wearable chest vest integrated with three novel textile-based electrodes for recording two channel ECG from which HR was derived. RR was derived from a sensor integrated with the vest that records chest expansions. SpO2 was recorded from the pulse oximeter probe of the HPHC physiological monitoring system from the left ear lobe. To assess the type and severity of motion sickness symptoms experienced during the run, the participants were administered motion sickness assessment questionnaire (MSAQ) immediately after the run. MSAQ is a 16-item questionnaire, each rated on a 9-point scale, which assesses multiple dimensions of motion sickness.[6] The questionnaire yields percentage scores in the form of an overall motion sickness score (OMSS) and subscale scores for the four distinct dimensions of motion sickness, namely, gastrointestinal (G), central (C), sopite related (SR), and peripheral (P) symptoms.

Experimental protocol

The participants were instrumented and seated in the gondola of HPHC. They were strapped to the seat with the 5-point harness and were instructed to stay relaxed. Their baseline parameters were recorded for 1 min (pre-run 1 G). Thereafter, they were subjected to simulated parabolic flight profile that involved exposure to 20 repetitions of 10 s hypogravity (+0.5 Gz) periods, sandwiched between 15 s hypergravity (+2 Gz) periods [Figure 1]. The gravity transitions between hypergravity and hypogravity periods during the centrifuge runs were completed within 3 s. Post-run parameters were recorded after termination of the run (post-run 1 G). After the completion of the centrifuge run, they were asked to rate the severity of their motion sickness symptoms on MSAQ. Their subjective feeling of weightlessness was also collected, which was rated on a scale of 1–10.

- A segment of the simulated parabolic flight profile showing different gravity phases.

The data of pre-run 1 G and post-run 1 G period were averaged separately. Actual parabolic flights, by design, include hypergravity periods before and after microgravity periods and thus influence each other. Hence, the data from the hypergravity phases immediately before and after the hypogravity periods were analyzed to account for this interaction. Accordingly, the data of hypergravity and hypogravity periods from the entire profile were averaged to three groups: The average derived from the last 5 s segments of all the hypogravity periods as “0.5 Gz hypogravity;” the average derived from the last 5 s segments of all the hypergravity periods as “Late 2 G;” and the average derived from the first 5 s segments of all the hypergravity periods as “Early 2 G” [Figure 1].

Statistical analysis

All data sets were checked for normality with histograms, Q-Q plots, and normality tests (Shapiro—Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov). A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was applied to determine the effect of gravity (independent variable with five levels: Pre-run 1 G, late 2 G, 0.5 Gz hypogravity, early 2 G, and post-run 1 G) on the physiological parameters (dependent variables: HR, RR, and SpO2). Furthermore, the effect of repeated exposure to hypogravity (independent variable with three levels: Pre-run 1 G, 10th and 20th loops of hypogravity) on the physiological parameters (dependent variables: HR, RR, and SpO2) was also analyzed using one-way repeated measures ANOVA. In the above analysis, for comparison with pre-run 1 G data, the 10th and 20th loops of hypogravity phases were chosen to ensure equivalent time difference between the groups to eliminate any sampling bias. Post hoc analysis was carried out using Bonferroni correction. The level of significance was kept at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSSv20.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics (Mean ± SD) of physiological parameters in different gravity phases are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | n | Pre-run 1 G | Late 2 G | 0.5 Gz | Early 2 G | Post-run 1 G | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | 12 | 80.9±11.9 | 101.6±24.3* | 77.7±15.9# | 94.6±19.3*#+ | 82.3±13.9#^ | <0.001 |

| RR (/min) | 12 | 18.7±4.3 | 19.9±5.3 | 20.0±5.4 | 19.9±4.5 | 18.1±5.3 | 0.148 |

| SpO2 (%) | 11 | 97.9±0.7 | 97.7±0.6 | 97.7±0.7 | 97.7±0.5 | 97.8±0.6 | 0.199 |

Comparison of physiological parameters across different gravity phases revealed statistically significant differences in HR (F [1.816, 19.974] = 22.167, P < 0.001, η p2 = 0.668). Post hoc analysis revealed that the HR increased significantly during both late 2 G (P = 0.011) and early 2 G (P = 0.032) phases compared with pre-run 1 G values. The HR showed significantly higher values during the late 2 G phase compared with early 2 G phases (P = 0.031). HR reduced significantly during the hypogravity phase in comparison with both late 2 G (P < 0.001) and early 2 G (P < 0.001) hypergravity phases. No significant differences were observed in both RR (F [4, 44] = 1.789, P = 0.148, ηp2 = 0.140) and SpO2 (F [2.378, 23.775] = 1.708, P = 0.199, ηp2 = 0.146) across different gravity phases.

The descriptive statistics (Mean ± SD) of the changes in the physiological parameters with repeated exposures to hypogravity phases at 10th and 20th loops are shown in Table 2.

| Variables | n | Pre-run 1 G | 10th loop | 20th loop | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (bpm) | 12 | 80.9±11.9 | 77.7±16.1 | 69.7±13.1*# | 0.01 |

| RR (/min) | 12 | 18.7±4.3 | 21.3±8.2 | 18.7±8.7 | 0.478 |

| SpO2 (%) | 11 | 97.9±0.7 | 97.7±0.5 | 97.6±0.8 | 0.199 |

Comparison of physiological parameters between prerun 1 G, 10th and 20th loops of hypogravity phases revealed statistically significant differences in HR (F [2, 22] = 5.672, P = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.810). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant reduction in HR during the 20th loop of hypogravity phase, compared with both pre-run 1 G values (P = 0.023) and 10th loop values (P = 0.042). There were no significant differences observed in both RR (F [2, 22] = 0.763, P = 0.478, ηp2 = 0.065) and SpO2 (F [2.378, 23.775] = 1.708, P = 0.199, ηp2 = 0.146) parameters on repeated exposures to hypogravity phases.

Motion sickness symptoms experienced during the run were assessed using MSAQ. The OMSS of the participants calculated from MSAQ ranged from 11.1% to 47.9%, with a group mean value of 23.6%. The subscale scores derived from MSAQ are shown in Figure 2. One participant developed vomiting after termination of the run. The subjective rating was also collected from the participants after the run on their experience of weightlessness on a scale of 1–10. All participants rated their experience between 4 and 6, with maximum number of participants giving a rating of 5 [Figure 3].

- Box and Whisker plot with interquartile ranges showing MSAQ scores. (MSAQ: Motion sickness assessment questionnaire, G: Gastrointestinal, C: Central, P: Peripheral, SR: Sopite related, OMSS: Overall motion sickness score).

- The frequency distribution of ratings of subjective feeling of weightlessness.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed at evaluating the feasibility of utilizing human centrifuge for simulation of parabolic flight on ground. The utilization of centrifuge for simulating such hypogravity states is explained by the “Reduced Gravity Paradigm” hypothesis[7] which states that the physiological responses evoked in a biological system as a result of transition from a normogravity state to microgravity state can be achieved by transition from a hypergravity to normogravity state. A typical parabolic fight involves an aircraft flying 30–60 parabolic trajectories, producing periods of absolute weightlessness (0 G), sandwiched between hypergravity periods (+2 G), with each gravity phase sustained for approximately 20 s.[3] Since the total resultant gravitoinertial acceleration below 1 G cannot be simulated on ground, achieving the gravitational unloading in the +Gz axis to <1 G for the simulation of hypogravity periods necessitated imparting additional acceleration in a different axis, +0.95 Gx in our study.

The centrifuge profile created in our study involved exposure of participants to 20 loops of hypogravity periods (0.5 +Gz and +0.95 Gx) sustained for 10 s each, sandwiched between hypergravity periods (+2 Gz) sustained for 15 s each, producing hypergravity to hypogravity transitions in Gz axis similar to that of an actual parabolic flight. The duration and magnitude of acceleration values were arrived at after trying different combination of acceleration magnitudes, onset/offset rates; considering the limitations of HPHC. The duration of each gravitational phase in our study was minimized to limit the total exposure time to prevent overt motion sickness symptoms which might result from Coriolis effects of the centrifuge. Literature review of actual parabolic flight studies revealed the number of parabolas to which participants were exposed to, ranged from a minimum of 8 to a maximum of 15.[8-10] Since the duration of each gravitational segment was reduced in our study, the number of parabolas to which the participants were exposed was increased to 20 to obtain a similar magnitude of physiological response.

In the present study, HR increased during hypergravity periods and reduced during hypogravity periods, indicating that HR varied proportionally with G. Similar changes in HR responses have also been reported from actual parabolic flight studies.[8,9,11-14] Hypergravity causes a drop in transmural pressure and reduction in the stretching of the arterial baroreceptors. These changes result in unloading of arterial baroreceptors leading to sympathetic stimulation, finally resulting in increased HR. Opposite changes are evident during hypogravity. Reduction in the gravity produces thoracic fluid shift and distension of thoracic and cephalic vasculatures. This causes increased stretching and loading of the baroreceptors. The resulting stimulation of arterial baroreceptors leads to sympathetic withdrawal and increased parasympathetic output, finally reducing the HR.[15-17] The HR responses observed in our study could be attributed to the above baroreceptor reflex mechanism. HR was also found to show significant difference between early 2 G and late 2 G phases of hypergravity period. The lower HR during the early 2 G phase compared to late 2 G phase may partly be attributed to the transitory effect of the preceding hypogravity phase where reduction of HR was observed.

In our study, HR at the 20th loop of hypogravity phase was significantly reduced compared to both pre-run 1 G and 10th loop of hypogravity phase, indicating that HR decreased at the end of repeated exposures to hypogravity. Kowalczuk et al. in their centrifuge simulated parabolic flight study also reported of similar progressive decline in HR with repeated exposures to 0 Gz periods.[4] Mukai et al. also reported similar HR changes in their parabolic flight study. They observed a decrease in thoracic fluid index with each exposure to microgravity indicating a progressive increase in thoracic fluid shift and thereby central venous pressures.[18] During the hypogravity phases in our study, there was an additional +0.95 Gx component acting parallel to the hydrostatic fluid column of the blood vessels in the thighs of the seated participants. This could have resulted in increased hydrostatic pressure of the fluid columns, further accentuating fluid shift toward thoracic vasculature with each hypogravity exposure. This “hydrostatic column effect” is similar to that reported in Astronauts during their pre-launch semi-supine posture, which gets accentuated further during the launch phase of spaceflight due to increase in Gx acceleration.[8,9] The reduction in HR as a result of hypogravity observed in our study could be attributed to the cumulative effects of the above-mentioned mechanisms. The HR reduction also indicated possibly of physiologically less stressful successive gravity transitions than their respective preceding gravity transitions.

Another important observation in our study was absence of significant differences in RR and SpO2 with different gravity phases or with repeated exposures to hypogravity. Paiva et al.[19] and Edyvean et al.[20] also reported similar findings in the temporal pattern of breathing with different gravity phases in their parabolic flight experiments. Studies suggest that exposure to hypergravity is associated with a reduction in tidal volume and an increase in breathing frequency.[17] Armstrong and Heim reported appearance of an increase in breathing frequency at + 2 Gz–+3 Gz.[21] However, low levels of increments in accelerations are well tolerated and changes in ventilation and pattern of breathing are small.[22] Hypogravity phase simulated in our study exposed the participants to combined +0.5 Gz and +0.95 Gx accelerations. This gravitational state could be considered similar to that experienced on attaining a supine posture (0 Gz and +1 Gx). Ventilatory characteristics including respiratory rate are not affected by changes in posture from upright to supine.[23,24] The absence of RR changes observed in our study may be attributed to above findings.

Similarly, no changes in SpO2 were observed in our study. Any fall in the arterial oxygen saturation associated with +Gz acceleration is due to perfusion of unventilated basal lung alveoli due to increased weight of the lung.[17,22] However, available literature indicates that any such reduction in SpO2 becomes apparent only at +3 Gz and increases with the magnitude and duration of imposed acceleration.[17,22] Since the simulated acceleration in our study was only +2 Gz, no significant fall in the SpO2 was an expected outcome. In microgravity conditions, the ventilation-perfusion mismatches are still persistent and gas exchange is not different from that seen in 1 G condition.[25] Similar findings were also reported by Smith et al.,[26] wherein no changes in SpO2 were observed between simulated microgravity phases and the 1 G values during their parabolic flight exposure.

The type and severity of motion sickness symptoms experienced by the participants were also assessed in this study. The participants were asked to keep their head stable during the centrifuge runs, to minimize the aggravation of motion sickness. Out of 12, only 1 participant (8.3%) developed vomiting immediately after the termination of the run. Golding et al.[27] reported the prevalence of individuals who developed vomiting to be 12% in their actual parabolic flight study. Assessment of motion sickness symptoms experienced during centrifuge simulated parabolic flight may provide some indication regarding the susceptibility of individuals to develop motion sickness in actual parabolic flights. Furthermore, the possibility of using such ground based modalities in providing adaptation to such individuals could also be explored through future research. These measures may help in increasing the effectiveness of parabolic flight training by aiding the selection of suitable candidates and in providing pre-adaption to the unusual patterns of motion stimuli encountered during actual parabolic flights.

In the present study, the subjective rating of weightlessness experienced by the participants during the centrifuge simulated parabolic flight ranged from 4 to 6. This feeling of weightlessness experienced can be attributed to the axial unloading caused by the reduction in the magnitude of +Gz acceleration from 2 to 0.5 G. The participants reported that weightlessness was experienced particularly during transition from hypergravity to hypogravity state. After the transition, the participants reported that the sensation during the hypogravity period was similar to that of the supine posture. This was because of the +Gx acceleration (0.95 G) imparted during the hypogravity period which was necessary to achieve the gravitational unloading in the +Gz axis. Although the acceleration profile in our study was designed to match that of an actual parabolic flight, the gravitational state achieved in our study was not that of absolute weightlessness. However, such hypogravity simulations may provide an opportunity to explore the possibility of conducting research in various subgravity states (Martian – 0.38 G and Lunar – 0.16 G) on ground, similar to that being presently explored through actual parabolic flights.[28]

CONCLUSION

It can be concluded from the results of our study that HR increased during hypergravity conditions and reduced during hypogravity phases, an expected outcome during parabolic flight. The significant reduction in HR during the 20th loop of hypogravity period compared to 10th loop and pre-run 1 G conditions indicate a possible association with the duration of exposure. No significant changes in RR or SpO2 were observed in any of the experimental conditions. These observations indicate that findings of our study are comparable to actual parabolic flight studies with respect to changes in HR, RR and SpO2. All the participants reported experiencing some degree of weightlessness during the transition to hypogravity and various motion sickness symptoms during the simulation. Centrifuge simulated parabolic flight may serve as an alternative ground-based simulation model for microgravity research and training platform for the preparation and possibly promote prior adaptation to subsequent actual parabolic flights and space missions for space crew.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate consent from the participants.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Possible methods of producing the gravity-free state for medical research. J Aviat Med. 1950;21:395-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parabolic flight as a spaceflight analog. J Appl Physiol. 2016;120:1442-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The dynamics of parabolic flight: Flight characteristics and passenger percepts. Acta Astronaut. 2008;63:594-602.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Application of human centrifuge to simulate parabolic flight: Early experience. Pol J Aviat Med Bioeng Psychol. 2019;24:21-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adaptation of systemic and pulmonary circulation to acute changes in gravity and body position. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2019;90:688-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Questionnaire for the assessment of the multiple dimensions of motion sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001;72:115-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centrifuges for microgravity simulation. The reduced gravity paradigm. Front Astron Space Sci. 2016;3:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acute hemodynamic responses to weightlessness in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;29:615-27.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute hemodynamic responses to weightlessness during parabolic flight. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:993-1000.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atrial distension in humans during microgravity induced by parabolic flights. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1862-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular and valsalva responses during parabolic flight. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1957-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sympathetic outflow to muscle in humans during short periods of microgravity produced by parabolic flight. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R419-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arterial pressure in humans during weightlessness induced by parabolic flights. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:928-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of an acute increase in central blood volume on cerebral hemodynamics. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309:R902-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physiology, baroreceptors In: Stat Pearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular physiology In: Ward J, ed. Ernsting's Aviation and Space Medicine (5th ed). United States: CRC Press; 2016. p. :13-28.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Long duration acceleration In: Ernsting's Aviation and Space Medicine (5th ed). United States: CRC Press; 2016. p. :131-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular responses to repetitive exposure to hyper-and hypogravity states produced by parabolic flight. J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;34:472-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung volumes, chest wall configuration and pattern of breathing in microgravity. J Appl Physiol. 1985-1989;67:1542-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung and chest wall mechanics in microgravity. J Appl Physiol. 1985-1991;71:1956-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Effects of Gravity and Acceleration on the Lung London, France: Advisory Group for Aerospace Research and Development Neuilly-Sur-Seine; 1970.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of changes in functional residual capacity with posture on mouth occlusion pressure and ventilatory pattern. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977;116:895-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of posture on ventilation and breathing pattern during room air breathing at rest. Lung. 1987;165:341-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microgravity and the respiratory system. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1459-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring tissue oxygen saturation in microgravity on parabolic flights. Gravitat Space Res. 2020;4:2-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, predictors, and prevention of motion sickness in zero-G parabolic flights. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2017;88:3-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular autonomic adaptation in lunar and Martian gravity during parabolic flight. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115:1205-18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]